What if I told you every bad experience you’ve had is your fault.

If you’re like me, you probably got defensive when you read that and usually blame most things on circumstance instead of on your own free will.

That idea is one that Carl Jung struggled with throughout his life as a psychiatrist. He dealt with thousands of patients who were depressed, anxious, scared, and needed help.

Person after person, after talking to the same types of people for years, eventually he found a pattern in their attitude: They all tried to take the least amount of responsibility for their suffering and they thought of themselves as highly virtuous.

It was almost like they were stuck in a bubble where everything was everyone else’s fault and they were just a victim to an unlucky circumstance. They even blamed “God”, or being itself for purposely creating all this evil against them.

The problem with blaming the world for your problems is that it puts you in a position where you can’t do anything to improve your current state. If it’s your fault, at least it means you’re the problem and you can improve yourself to improve your life circumstance.

But if it’s the universe’s fault, well then guess what, you’re screwed. How are you, 1 person gonna change the fate of the universe? Impossible, and it’s one of the reasons why people get flooded with negative emotion, because the possibility of change becomes hopeless.

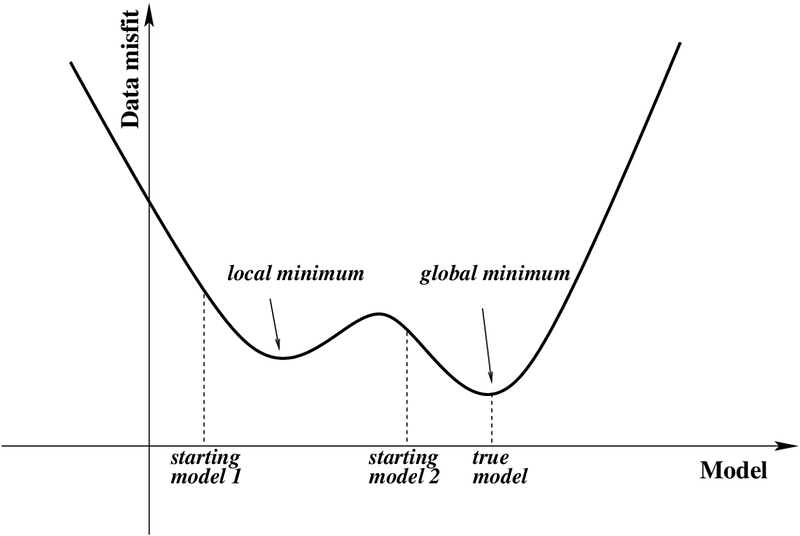

If you look at things from a biological perspective, what advantage does a lack of responsibility give humans? We’re hard wired to dislike change once we’ve figured out a way of doing things that works.

If using a spear to kill a fish works really well, then I’ll be less likely to try using a rock instead. That’s just the way we’ve evolved. It can be helpful in certain cases to be stuck on one way of doing things, but also unhelpful if the habit or belief doesn't make sense (like someone trying to convince you the flying spaghetti monster is real).

And that sense of avoiding change get’s worst as we age. Your brain loses it’s neuro-plasticity and can’t form new neural connections as easily. It’s why a bunch of old people hate the way we’re headed with computers and technology — because they are adapted to a different time and physically can’t understand current progress without extreme effort and openness.

Adopting the lack of responsibility mindset means not being open to change. Blaming everything else for your suffering means tricking your brain into thinking it’s right and not adapting your physical brain structure.

But with that mindset you’re stuck in the past and can’t accept the future. Everything changes while you stand still. It means you’re suffering to keep up while everyone’s having a good time, further making you feel like the universe is to blame.

Carl Jung understood this, and constructed a theory explaining the 3 parts of our psyche.

The Ego

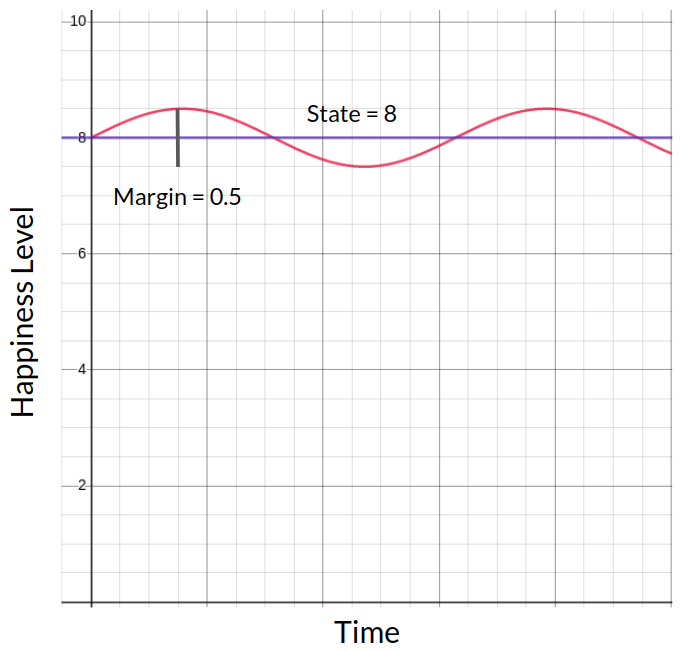

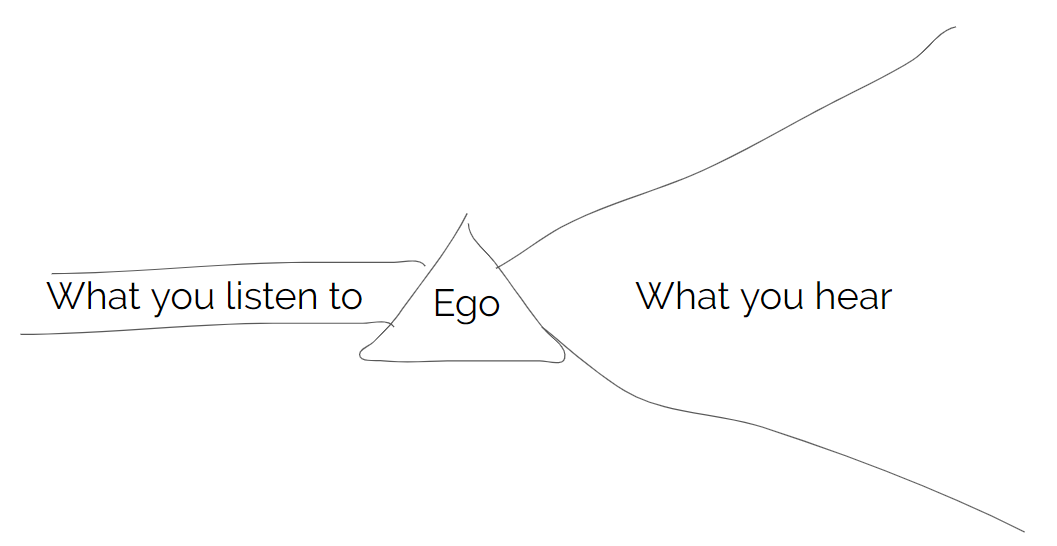

Also know as the “gatekeeper”, this part of the psyche is made up of memories, thoughts, and emotions.

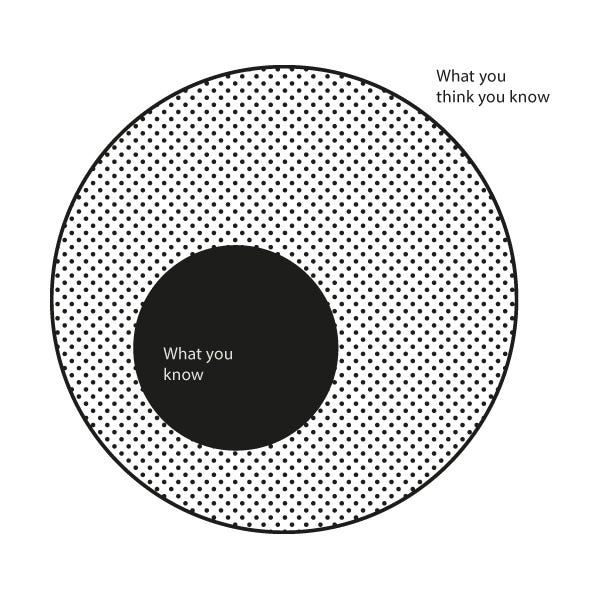

Thoughts + emotions + experience = complexes. Those complexes are like mental models we use to classify the information and stimulus we get on a daily basis.

There’s no way we could interpret everything we hear or read as truth - we’d be flooded with paradoxes. Instead, we use those complexes to decide whether we should take something at face value or not.

That bias gives us our individual identity. I wouldn’t be Luke without being sceptical and questioning things that don’t make sense to me. But that just comes from my experience of frequently finding flaws when I look deep enough. Other people have very different mental models based on their experience, each good and bad under different circumstances.

The individual Unconscious

This part of the psyche is just like the ego — it’s formed from a bunch of different complexes— but those complexes are forgotten and are hidden in the unconscious.

The more memories and emotions associated with a complex, the stronger it becomes.

In Hitler’s case, his negative experiences and negative emotional responses associated with foreigners made him idealise the German race and want to eradicate any signs of impurity in others.

That subconscious complex had kept getting reinforced and validated by new experiences and emotions to the point where his ideology spiralled out of control.

It’s a good example of how dangerous complex validation can be — especially when that complex has already been established. If you already have a cognitive bias against something, it’s likely your bias will fit the thing you’re judging and will hence further validate your bias.

“If you’re looking for negativity, it’ll come to you. If you’re looking for positivity, it’ll come too”

-me

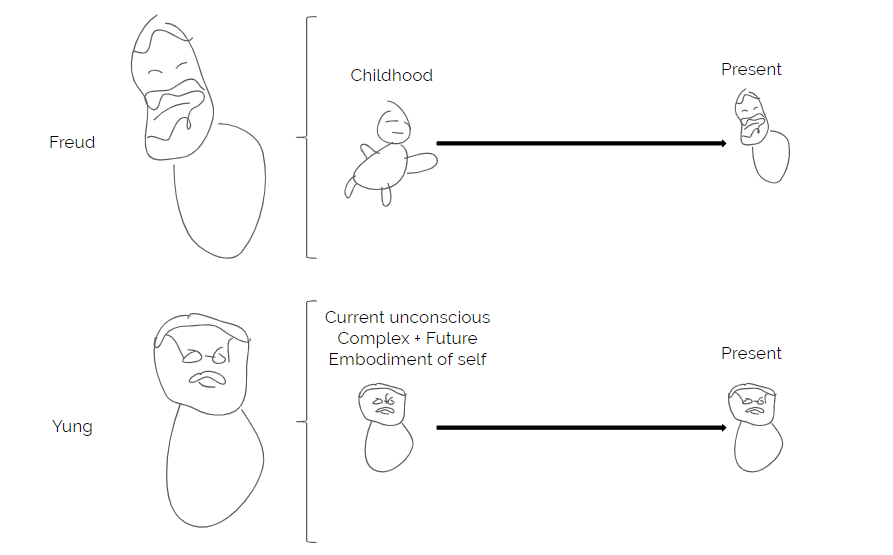

Sigmund Freud was a prominent figure in crafting Carl Jung’s philosophy. Jung worked under him for years until they diverged paths when he denounced some of Freud’s theories publicly.

Freud stressed a lot on the impact a child’s experience has on their adult life. His big thing was that all problems we deal with are a result of not being raised right as children and being exposed to childhood trauma.

Jung didn’t really think that was enough, and thought the present and the embodiment of the future into the current self + our deepest unconscious complexes had a much more to do with it.

It might be hard to think of the future embodying the present, but Jung believed that who we could be and who we strive to be directly transforms us into that person in the present — a much more optimistic view over Freud’s.

But that isn’t all they disagreed on.

The Collective Unconscious

Paradoxically, Jung also put a lot of stress on the past and it’s effect on our current complexes. But instead of our complexes being a product of our childhood traumas and experienced past, he believed some were ingrained into our DNA through evolution.

He called them archetypes, fundamental ideas that are found across all societies.

According to him, there were many archetypes that are uni-present across all human beings because they universally apply to everyone’s life. Here are the 4 major ones:

- Persona → what your projected image on society is (ex: CEO, bar tender, housewife, etc.). He called it the “conformity archetype” because they are vast generalisations that give us a means of conforming to societal expectations.

- Anima/animus → mirror image of our biological sex (unconscious masculine in women and unconscious feminine in men). He believed that because we’ve worked so tightly in communities, we’ve mixed the two together, where now men are much more feminine and women are much more masculine.

- Shadow → our primitive animal personality seen as the evil side that only acts selfishly. It is the source of both creative and destructive energies.

- Self → unity of the individual across their complexes, both unconscious and conscious. He thought that the problems of modern life come from “man’s progressive alienation from his instinctual foundation”, the disunity of the self often caused by mixing anima/animus too much (women being too manly and men being too feminine).

Freud thought this was mumbo jumbo, and stuck to his theory on childhood trauma.

But I think that was Freud’s biggest mistake — he was too stuck up on his ideas and didn’t question them enough. He would come up with a hypothesis and be convinced it had to be the truth vs Jung who was constantly questioning his ideas.

After looking deeper into his hypothesis on the collective unconscious and into ancient and recent societies across the world, Jung realised all of them shared these same archetypes. It’s how he validated his hypothesis, will hard historical evidence.

Stories are a way of reinforcing certain actions by showing hypothetical positive or negative outcomes.

In Cinderella, Cinderella finds true love and happiness because of her good character whereas the evil step sister get their eyes picked out by crows (sorry, didn’t wanna draw this one).

These stories are a way of showing people the right way of conducting yourself in the world and the benefits you’ll get from acting in that way.

Jung looked into ancient myths, old stories across societies all over the world that would have never had contact with each other, and he found similar archetypes among all of them. Other than the 4 I mentioned earlier, here are some others:

- Mother

- Earth

- Birth

- Rebirth

- Child

- Death

- Power

- The hero

These would take a while to unpack, but out of all of them The Hero myth seems super interesting to me. No matter where you go, there’s always stories of a hero who concurs evil, and creates order out of chaos (known out of the unknown).

Jung used that textual evidence to validated his hypothesis on fundamental complexes we all have ingrained deep into our DNA.

Overcoming the Shadow

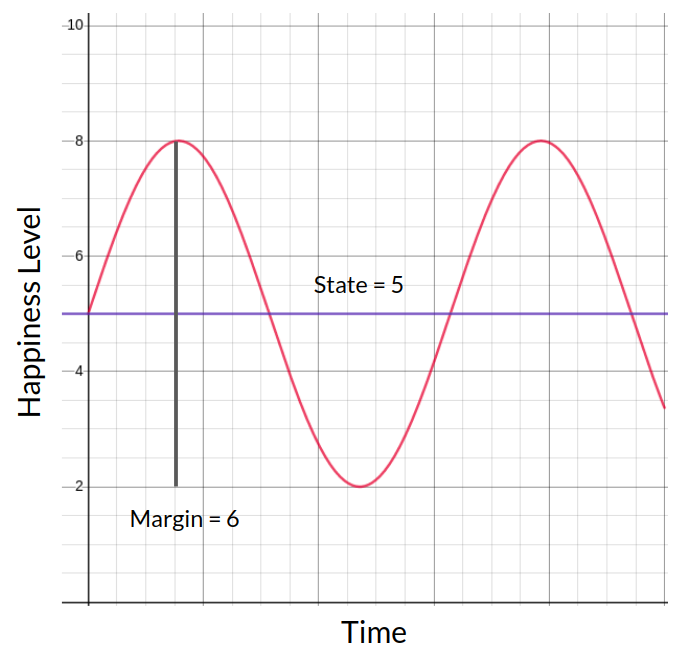

In a previous article, I talked about “Why you should stop expecting things”, basically explaining how expectation leads to betrayal and negative emotion that’s meant to force us to change our habits.

What do I mean by that? For ex: getting cheated on by your best friend makes you terribly sad and forces you to re-evaluate your trust in people and adjust it to fit that negative experience.

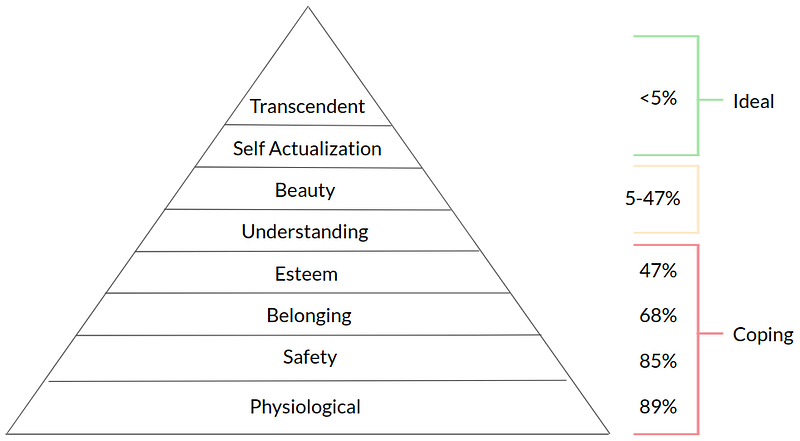

Jung believed that when it came to high neuroticism and overcoming negative emotion, a big piece came from a lack of responsibility and courage to face your mistakes.

We know that deep pain comes from betrayal, so Jung argues that taking responsibility for that betrayal and realising you could equally do the same is the cure for negative emotion.

It’s the acceptance of the shadow, understanding that you could do terrible evil, that gives you humility and makes you less prone to betrayal and more aware of your true motives.

“Your visions will become clear only when you can look into your own heart. Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.”

- Jung

That comes with understanding that under the right circumstances, you could’ve even been a Nazi concentration camp guard — and enjoyed it.

It’s the hard path to happiness

Basically admitting you could’ve been Hitler is completely against your human nature.

But being good only comes with the potential of evil. You can only be moral if you could do unmoral things. Being scarred of punching someone vs deciding not to punch someone are 2 completely different things. Same outcome, but completely different motives.

Everything is relative, and there wouldn’t be good without evil.

Until you take responsibility and understand you could do horrible things, you can’t be a fundamentally good person.

“The reason modern people can’t see God is that they won’t look low enough”

- Jung

That’s his most important message. Take responsibility. Understand how flawed and evil you could be, and you’ll be aware of when you’re doing evil and find it much easier to stop. The alternative is hiding that part of you and not realizing till it’s too late.

]]>